The world’s largest wealth fund may become a large green energy investor

Norway's new – not yet appointed – Prime Minister, Erna Solberg of the Conservative Party, may at first instance appear less occupied by global issues like climate change than her predecessor Jens Stoltenberg of the Labour party. But on a few critical climate issues she looks like more of a reformer than Mr Stoltenberg, in particular when it comes to what role Norway’s enormous Sovereign Wealth Fund could play in financing the transition to a low-carbon economy.

In the New Government's programme revealed this week, the coalition partners made the following statements regarding the $720bn sovereign wealth fund:

Norway's Sovereign Wealth Fund, officially called the Government Pension Fund Global (GPFG), is the world's largest sovereign wealth fund. Currently the fund is allowed to invest in listed equities, bonds and real estate. However, if the fund were allowed to expand its portfolio to include direct investments in assets like wind and solar plants and other infrastructure, this could potentially have a very significant impact on the total flow of capital to the renewable energy sector.

A number of organizations and institutions in Norway have for some time been advocating such a reform. Even the Fund's manager, Norway's Central Bank, has asked the Ministry of Finance to let it enter into direct infrastructure investments, so far without approval. However, last week an influential and unusual alliance of leading companies and organisations in finance, religion, renewable energy, environment and development, put the question on the top of the Norwegian agenda through a joint initiative. The Norwegian Government Pension Fund Global should start to invest directly in infrastructure for the production and distribution of renewable energy, was their message. Direct investments in renewable energy would be a good move on the basis of both a financial and sustainability perspective, they argue.

The group of signatories includes financial institutions such as KLP, Storebrand Asset Management, the Ulltveit-Moe Group, the green energy company Scatec (my employer), the Catholic Diocese of Oslo and a number of organizations in the field of environment and development: WWF Norway (World Wildlife Fund), The Norwegian Climate Foundation, The Development Fund, Future in our hands, Zero, Greenpeace, Friends of the Earth Norway and Young Friends of the Earth Norway.

In the letter, the signatories underline that other large European pension funds are already investing directly in renewable energy, and that the GPFG is very well positioned to do the same. The size of the fund, the long-term investment horizon and the fact that the fund does not have on-going liquidity needs, makes it possible for the GPFG to aim at investing directly in renewable energy projects, they say. Another argument to do so is that global warming threatens the long-term performance of the Pension Fund. With more extreme weather the international community must spend an ever increasing amount of resources on repair and adaptation, at the expense of investments that can yield higher productivity and hence good returns on financial investments.

A move by Norway's so-called Petroleum Fund into renewables would be significant, both directly and indirectly. According to Marius Holm, leader of Zero, "there are few other areas where Norway is able to contribute in such a relevant way to the global shift to green energy". The possible direct significance is derived from the sheer size of the Fund. According to the Ministry of Finance, the value of the Fund may rise to 1000 Billion USD by 2020.

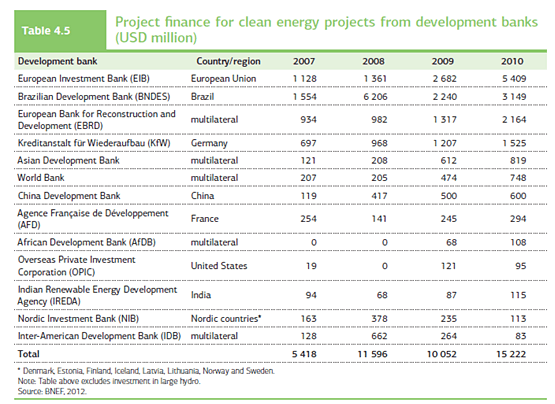

If the Fund is allowed to invest up to 5 percent – equal to the target set for its property investments – of its total assets into renewable energy-related infrastructure, the Fund could on average allocate in the range of 10 Billion USD per year to the green energy investment market from 2015 onwards. This is admittedly a modest amount compared to the $ 500 billion in yearly green energy investments which, according to the IEA, is required if we seek to limit global warming to 2 degrees. But it could still make Norway's SWF one of the worlds largest, if not the largest, single clean energy investor. In a recent IEA report development banks like the European Investment Bank, KfW, World Bank among others are highlighted as leading financial institutions in the green energy sector:

But the possible indirect effects are arguably more important than the direct ones. This is because the Fund by many is seen as a peer leader among the SWFs when it comes to governance and socially responsible investments. The total wealth of the world's Sovereign Wealth Funds amount to more than 5 billion USD, of which 60 percent belong to the world's oil and gas exporters. A decision to let Norway's Fund seek low-carbon direct investment oppurtunities, will most likely be followed by other SWFs. A few of them, like Singapore's Temasek and Abu Dhabi's, have already started. More long-term capital allocated to green energy will not by itself lead to more green energy projects, but the increased access to capital will lower the cost of capital to the sector and hence make many more greeen projects bankable.

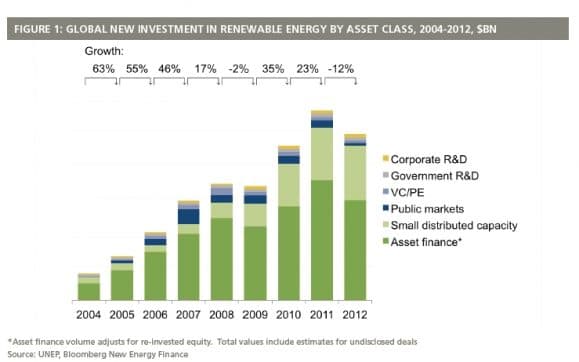

One of the questions to the new government is how a new mandate will be implemented and managed. Here a combination of vehicles and management partners can be foreseen. As shown in the table below from a recent Bloomberg/UNEP report the majority of investments in Renewable Energy are asset-backed, a framework that fits well with the purpose and time-perspective of the Fund.

One prudent approach for the Fund could be to team up with international development finance institutions (DFIs) like Norways DFI Norfund, the World Bank's IFC, etc, and co-invest into projects that satisfy the Fund's criteria. Similarly, the Fund can allocate mandates to private fund managers targeting green energy assets. The emerging market for Green Bonds should also be attractive for Norway's Sovereign Fund. Given the intrinsic attraction of renewable energy assets – low technology risk paired with long-term power purchase agreements – it shouldn't be difficult for the green energy managers to beat the Fund's average real return which has been in the range of 3 pct p.a. over the last years.

However, it should be noted that the new Government has yet to study the proposal, before making a final decision. New ideas like these have a tendency to be opposed by the powerful civil servants in the Ministry of Finance. The incoming government will hear arguments about costs and risks, whereas the real reasons for the opposition has more to do with the civil servants' perception of this as yet another fashion by popularity-seeking politicians. It is commendable and understandable that civil servants assume the role of "protector" of our savings, but in this case they should dig deeper into the issues at stake. Or, as Storebrand's CIO Jan Erik Saugestad put it:

«The management of long-term savings and pensions suits well with long-term investments such as those in infrastructure and in the energy sector transformation. There are therefore both financially and environmentally sound reasons for the GPFG to get a mandate to invest in these sectors".